Americans who were born in Afshar's City (Urmia)!

He Came Not Be Ministered Unto, But to Minister!

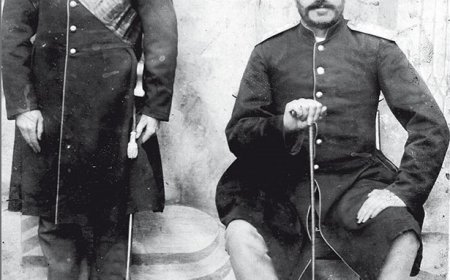

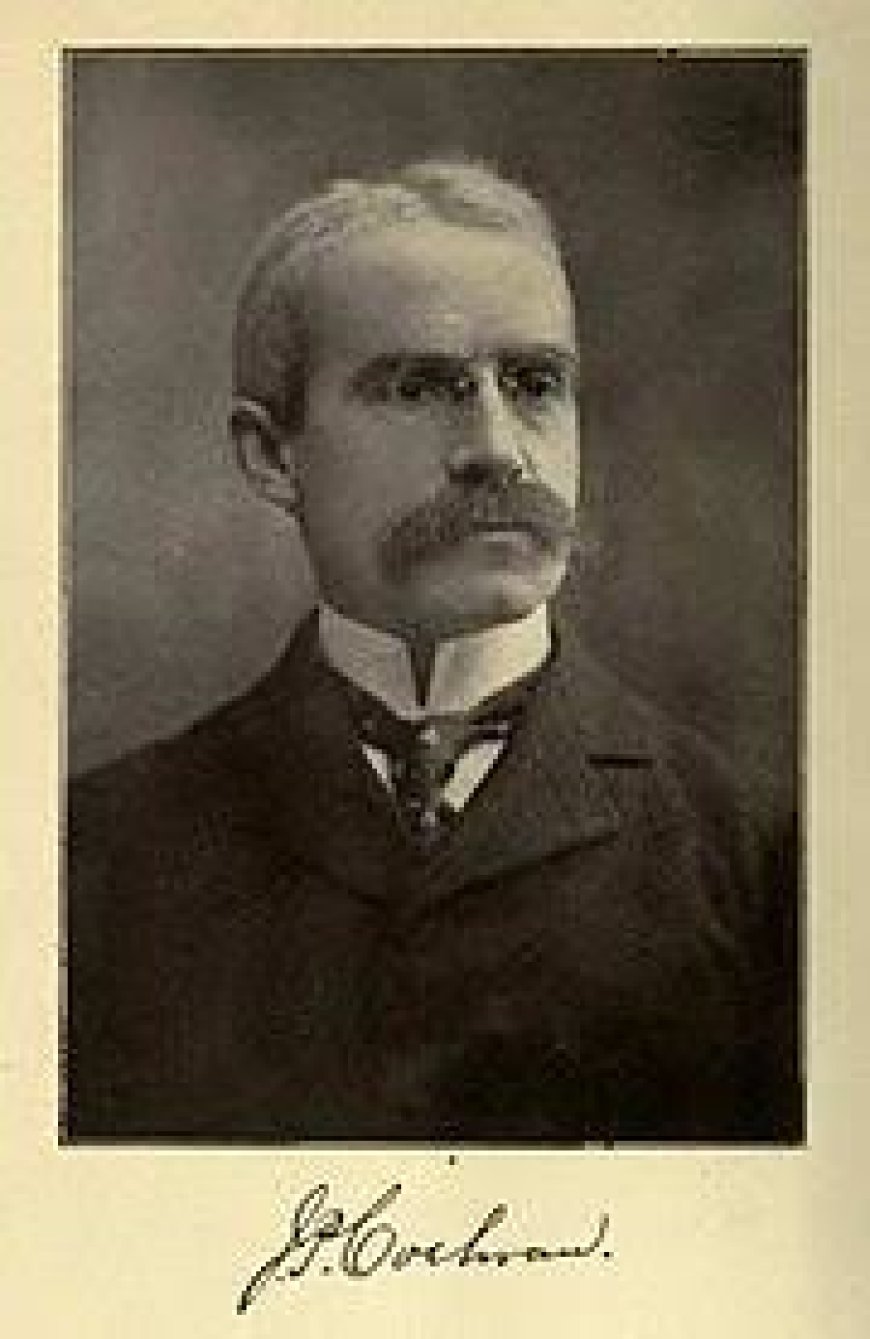

Joseph Plumb Cochran was a man woven from the rarest fibers of dedication, vision, and sacrifice—a child of missionaries, born into the rugged, romantic highlands of Persia, and destined to become one of its most beloved sons. Known to the people as "Hakim Sahib," or "The Master Doctor," Cochran was more than just a physician; he was a bridge between cultures, a healer of bodies and hearts, and a quiet revolutionary who helped shape the face of medical missions in the Near East.

Born on January 14, 1855, in the village of Seir near Urumia in northwestern Persia, Joseph was the son of Joseph Gallup Cochran and Deborah Plumb Cochran, American Presbyterian missionaries devoted to serving the Nestorian Christian community. His parents were no strangers to hardship they weathered plague, famine, political unrest, and personal loss with stoic grace. It was into this crucible of service and faith that young Joseph was born, inheriting not only a missionary legacy but also a deep love for the Persian people, whose language, customs, and struggles he came to know as his own.

From an early age, Joseph showed a remarkable blend of gentleness and steel. He was bookish, yes, but also spirited—a boy who played “doctor” with an uncanny sense of empathy, who rode on horseback across dangerous Kurdish plains, and who watched with solemn eyes as his parents ministered to the poor, the sick, and the marginalized. He grew up with the rhythm of prayers, hymns, and village visits, a child shaped by the missionary life not as an outsider, but as a son of the land.

Educated in America after his father’s death in 1871, Joseph returned to Persia with a medical degree and a calling as clear as the mountain springs of Seir. In 1879, he established what became the first modern Western-style hospital in Persia. But he didn’t stop there—he went on to found a medical college that trained Persian doctors, many of whom were Christians and Muslims alike. His approach was revolutionary in its time: he saw no religious barrier to healing and held every human life as sacred. To train locals, not just treat them; to empower, not patronize—this was Cochran's subtle yet profound rebellion against the colonial mindsets of his age.

His life was anything but easy. He weathered waves of famine, political turmoil, Kurdish invasions, and resistance from both the Persian government and conservative elements within the local church. And yet, he remained. For over 26 years, Cochran worked tirelessly from the dusty streets of Urumia to the snow-covered paths of mountain villages, never seeking recognition, never writing his own name in headlines, but carving it deep into the hearts of a people who called him simply, “Hakim Sahib.”

His home was a place of hospitality and his presence a balm. Even in his final illness, stricken by typhoid, he never complained he simply faded, as humbly as he had lived, on August 18, 1905. But his legacy did not die. His hospital endured, his college endured, and the seeds he planted grew into generations of medical professionals who continued to serve their people long after his passing.

Cochran's story is not just one of missionary zeal, the tale of a bridge-builder, a healer, and a visionary. He saw not strangers but neighbors; not patients but brothers and sisters. And in doing so, he helped Persia see itself anew, through the clear, compassionate lens of Christ-like service.

To know Joseph Plumb Cochran is to witness what it looks like when faith walks in the dust and heals with its hands. His was a life of sacred ordinariness, of greatness carried out in quiet obedience and in the hearts of the Persian people, the name “Hakim Sahib” still echoes, like a prayer answered long ago.

What's Your Reaction?